I have written posts about what a share of stock represents and how stock trades work, but I have never given a breakdown on how corporate bonds work.

Like stock, companies use bonds to raise funds for any number of reasons. When a company raises funds with stock, they are giving away ownership in the company in exchange for they cash. With bonds, the company is only making a promise to pay the funds back, with interest.

Lets say company X needs to raise $1 billion to build a new plant. X is privately held and has no stock ownership outside of the company founders. X is a large company that is worth $10 billion, as determined by a private auditor. The company’s cash flows are strong and the company has healthy sales and profit growth.

To build the company, X’s owners can issue stock for $1 billion, which would give away 10% control of the company. That $1 billion would not have to ever be paid back. Alternatively, they can borrow $1 billion from investors and pay them back with interest. Due to the company’s credit rating, they have a 4% risk premium over the risk free rate (the Federal Reserve long term t-bond rate). If the risk free rate is 4%, X would have to pay 8% interest to borrow.

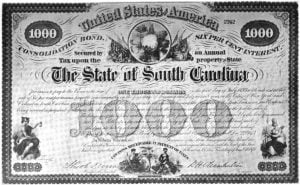

They decide to go along with the bond issue and issue $1 billion in new debt. Through the assistance of lawyers, accounts, and investment bankers, the company issues 1,000,000 20 year 8% coupon bonds with a face value of $1000 each. That means an investor can buy one or more for $1,000 each with 8% interest paid semi-annually. The company keeps the $1,000 from each investor for the time being.

If you buy one of these bonds at the time it is issued at face value, you are now owed the $1,000 plus interest from the company. Twice per year, the company will pay you $40. Your $80 per year, or 8%, is called a coupon payment. Some bonds are called “no coupon bonds” and are sold at a discount to make up for the interest.

At the end of the 20 years, called the bond maturity, the bond holder is paid the final $40 payment in addition to the $1,000 principal. Now, you, the bond holder, have earned 8% interest have all of your money back.

The risk to you is that the company will go broke and not be able to pay you back. Some bonds are “secured bonds”, and have an asset that will be sold to pay back investors. Others are not secure, and are only guaranteed by the company’s good credit. The risk level of the company determines the interest rate paid. People demand a higher interest rate for risky bonds than for safe bonds.

What if you buy a 20 year bond for $1,000 and you decide you need your money back sooner? If the bond is traded on the secondary bond market, you can sell the bond for its current value. Assuming interest rates are still yielding 8% for that company’s bonds, you can sell the bond for $1,000 at any time as long as there is a buyer. That buyer will then receive the 8% coupon. Most stock brokerage firms give their customers access to buy new bonds and buy and sell bonds on the secondary bond market.

That sounds pretty simple, right? It is, assuming interest rates are always 8%. When interest rates rise, the price of a bond goes down When interest rates fall, the price of a bond goes up. The price, that $1,000 if interest rates do not change, impacts the bond’s yield to maturity. People demand that a bond pays a yield that matches current market conditions. If someone gives you $900 for the $1,000 face value bond (a 10% discount), they are going to get a higher yield to maturity than someone paying $1,000. The calculator of YTM is very complicated, unless you have a fancy financial calculator (about $20) or a finance degree. Fortunately for you, I found this free YTM calculator online.

If you are thoroughly confused, have any questions, comments, or stories to share, please do so in the comments.

Comments are closed.